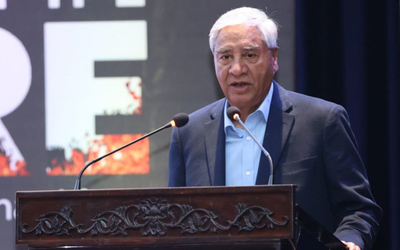

These days, K.P. Oli, the prime minister-in-waiting, spends most of his time defending the democratic credentials of his party, the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist Leninist. Oli’s defence is mainly a response to the Nepali Congress campaign during the election that the UML-led alliance would impose a totalitarian regime. He has also sought to question the Nepali Congress’s democratic credentials. “Nepali Congress took more than three months to hand over power to the Maoists who had emerged as the single largest party in 2008,’’ Oli reminds the people.

Oli seems to believe that Nepali Congress chief and Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba is delaying the transfer of power to his party even a month after election results were declared. This, he feels, is unconstitutional. However, Oli’s reference to 2008 may trigger a much wider debate and bring the inadequacies of the constitution to the fore. It could provoke interesting readings, especially at the present juncture when the very architects of the constitution are confused about its implementability.

Nepali Congress leader G.P. Koirala had continued as prime minister from June to mid-August 2008 even though the Maoists had won the election. The Koirala government took contentious decisions, including removal of the monarchy, by moving an official resolution in the newly constituted parliament. Koirala and his supporters ignored suggestions from constitutional experts that they had no right to exercise executive powers in the new House. Ever since, the decisions made by a few persons in power has been the biggest determinant in Nepal’s politics, no matter what the constitution says. Besides, it has now been proven that the constitution is vague and unclear on many key issues including government formation. And, no one is better qualified than Oli to offer a victim’s perspective.

After much wrangling, political parties have agreed to give the present government, a caretaker by all accounts, the right to name the temporary capitals of seven provinces and governors so that governments and legislative bodies could be formed. Mobilisations are taking place in different parts of the country to have their favourite city/town named as provincial capital. However, the outside world seems blind to all these problems, some of which could be a source for future deadlocks and crises, and wants to analyse the post-poll scenario solely as a victory of the pro-China Left alliance at the cost of India, earlier perceived to be a hegemon.

While Oli fears that the delay in the transfer of power may encourage outside forces to subvert the poll outcome and ruin his chances to become prime minister, China is visibly active, promising help to build industrial estates in all the provinces, including a Rs 333bn IT park in Jhapa, Oli’s home turf. These are expected to generate 80,000 jobs in five years.

China’s reading of the poll outcome seems to be that it is welcome to expand its development activities in Nepal. But Nepali actors are coming to the conclusion that the power-sharing practice which started a decade ago calls for a serious review. If Oli can raise past mistakes, others too could do so in the future, and perhaps, in a more aggressive manner. That would mean a return to chaos and uncertainty.

Coutesy: Indian Express

Yubaraj Ghimire

Ghimire is a Kathmandu based journalist.

- Manmohan Singh And The Churn In Nepal

- Jan 08, 2025

- Why ‘Revolutionary’ Communist PM Prachanda Went To Temples In India

- Jun 08, 2023

- Why China Is Happy With Nepal’s New PM

- Jan 03, 2023

- Prachanda Sworn In As PM: New Tie-ups In Nepal, Concern In India

- Dec 27, 2022

- Young TV Anchor As Its Face, RSP Rise Takes Nepal By Surprise

- Nov 23, 2022