Nepal’s history in recent decades has been marked by tumultuous events and transformations, and its relations with India by sharp fluctuations. Many books on both subjects have been written by scholars and foreign policy practitioners, Nepalese as well as Indian. Yet, too many unanswered questions remain, about the hows and whys of the past, the depth and challenges of present trends, and prospects for the future, in an increasingly uncertain post-Covid world.

Nepal registered several significant turning points in a relatively short span of time—among them achievement, at last, of full-fledged multi-party democracy after two popular upheavals and not a little help from across the southern border; a peaceful negotiated end to ten years of violent Maoist insurgency and the mainstreaming of Maoists into the democratic polity; adoption of a Constitution (albeit somewhat imperfect and hastily rushed through); a peaceful and in the end dignified exit of the institution of monarchy; the assertion of a new identity as a secular federal democratic republic.

Nepal now seems stuck in an unending transition. Thoughtful Nepalese commentators who were in the forefront of those demanding change are the first to voice their acute sense of disappointment at how things are turning out—the poor quality of democracy, rampant corruption and mal-governance, institutional failures, economic mismanagement and chronic instability punctuated with revolving-door governments and little pretence of ideological consistency or adherence to political commitments.

Nepal’s internal institutional shortcomings are a cruel reality. Also cruel is the realisation that for democracy to be meaningful, it is not enough to have regular and reasonably credible elections or even a free press and the right to dissent, which undoubtedly exist to a laudable degree in Nepal today. Unless there are independent institutions which cannot be remote-controlled by the government of the day, there is a real danger of democracy becoming a caricature of itself.

Nevertheless, there is hope within and among friends outside Nepal, especially India, that it is on the right track, and that with patience, perseverance, experience and support, the kind of leadership and direction it desperately needs will emerge, and Nepal will experience a speedier and smoother transition to a minimum desirable level of governance and inclusive development.

There is also undoubtedly space for India and Nepal to jointly create a sustainable positive trajectory for bilateral ties which would do more justice to their exceptionally rich and unique civilizational links and economic complementarities and make a more meaningful contribution to a stronger sub-region.

We have attempted in this book to analyse how the situation unfolded in the way it did, and as to whether the principal actors (including India) might help shape a better future in keeping with the expectations and needs of the people on both sides of the border.

Both countries owe it to themselves to revisit the past and introspect, even if it means asking uncomfortable questions. It is more necessary than ever before to draw lessons from the past, for it has repeated itself far too often. We do need to reimagine, perhaps to “repurpose” an age-old relationship, so that it can fulfill its real potential in a geo-political and geo-economic landscape so completely different from the one it inherited when the British left India in 1947, and yet it is the latter which has somehow continued to shape mindsets and policies on both sides for so many decades.

One understanding that hopefully will flow out of this study is that realpolitik, bargaining style diplomacy of the transactional kind and knee-jerk responses need not and cannot be the basis for relations between two countries such as India and Nepal, with such unique and deep historical, familial, religious, cultural, geographical and economic ties.

Irritants, potential or real (including longstanding ones like the 1950 Treaty) and differences (for example on the border, which appears to be devoid of chances of a political or diplomatic solution given the resolution passed by Nepal’s Parliament), can and should be sought to be sorted out in the way hiccups within a family are tackled, keeping the basis as well as continuing need of unshakeable bonds always in mind.

Sporadic attempts through normal diplomatic exchanges on such issues have been going on for some time, with no signs of progress. A Track 2 initiative (High Level Expert Group) blessed by both Prime Ministers was set up a few years ago and managed to prepare a confidential joint report with recommendations, but the Report has yet to be presented to the Prime Ministers because of the controversy that would result from non-implementation.

If such issues are discussed keeping the larger picture of an unbreakable age-old relationship and a vision of long-term interests always in mind, they will hopefully be subsumed by the latter, just as the major irritant of the Tanakpur Barrage constructed by India was subsumed by the larger vision of the Mahakali Treaty of 1996 which, unlike the former, was negotiated in a spirit of equality and respect for mutual interests, needs and sensitivities.

In that sense, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s relaxed and friendly response to Nepal’s strong objections to his inauguration of roads in border areas now claimed by Nepal, recommends itself over exchanging maps dating back to East India Company or British India days (Our History, Their History, Whose History? to borrow the title of Romila Thapar’s book), or issuing stern official statements and presenting counterclaims, which would be a standard official reaction.

Similarly, Nepal Ambassador Dr Shankar P Sharma’s attendance of a New Delhi function to celebrate consecration of the Ram Mandir at Ayodhya, and his reflection that Nepal’s parallel claim to Ram’s birthplace being in Nepal (former PM KP Sharma Oli had in fact earlier protested that India was ‘manipulating history’ to deny Nepal its rightful claims) should be taken simply as a confirmation of the rich shared cultural links between the two countries, commends itself over the strident condemnation of Oli’s claim in India.

We realise that some of our assessments and assertions will be contested. We are confident however that on many issues, some facts which are not yet in the public domain will get known in due course, and bear these out.

One area of special sensitivity has been Nepalese resentment of alleged Indian involvement in its internal affairs. Indian writers tend to lay a major portion of the blame on sections of the Nepalese elite who indulge in ultra-nationalism for short-term gains. We have tried to examine the facts as objectively as possible. It has been wisely said that “the essence of strategy is choosing what not to do.” This seems to have relevance for some actions of Nepal as well as of India, in the seven and half decades since India’s independence.

Indian diplomats would argue that its actions were well-intentioned and often in response to a felt need in Nepal. The fact however is that in hindsight, they might have best been avoided, for they have left a lasting impact on its perceptions of India.

We suggest this not as a mea culpa acknowledgement but rather in the spirit of External Affairs Minister S JaIshankar’s reflections in December 2023 (made in a wider context) of the importance of looking back and introspecting in order to keep correcting ourselves to set the foreign policy right, “It is very important for us, after 75 years of Independence, to introspect about… because often, we tend to think that the decisions which were taken, were the only decisions that could have been taken, which may not be entirely true.”

As for Nepal, its political leaders will hopefully realise sooner rather than later that it is entirely in that country’s long-term interests to consolidate its position as South Asia’s dependable partner in India’s quest to sit at the global high table.

At the time of writing, while India is led by a strong Prime Minister in Narendra Modi, Nepal is headed by the shrewd Maoist leader Prachanda leading a coalition, his Maoist party being the third largest, in a climate of political instability. There is a welcome trend towards pragmatic national self-interest in bilateral ties with India, major agreements have been reached on bilateral and sub-regional energy cooperation with welcome new emphasis on delivery and follow-up, one must keep one’s fingers crossed that this trend continues.

However, unfortunately, there seems to be a certain fatigue in expending political energy on self-destructive anti-India posturing, which cannot but pose new challenges to the continuance of a positive trajectory in bilateral ties. There are already ominous signs that the appetite for power at any cost may again lead to opportunistic political rearrangements with new uncertainties.

The relevance of the China factor in India’s foreign policy has only increased in recent years. Tibet is not the only reason for Chinese activism in Nepal. But Nepal’s traditional penchant for playing the China card to maximise benefits to itself from India has had to adjust to new factors. At the geopolitical level, the major Western powers are now much more alert to Chinese attempts to expand its influence and much more proactive in countering them as evidenced through mechanisms like the Quad and Indo-Pacific mechanisms. The Indian government itself under Prime Minister Narendra Modi is much more confident about dealing with China and much less vulnerable to blackmail tactics.

The Chinese have exposed themselves to Nepal’s political elite through fairly clumsy attempts at intervention in internal politics which have backfired on them. Even on the economic side, they are not finding it as easy as before to impress Nepalese businessmen, bureaucrats or politicians. Significantly, even seven years after BRI was launched and Nepal subscribed to it, not a single project has been negotiated by successive Kathmandu governments, each of which has found reasons to postpone decisions on Chinese terms.

Yet there is no reason for complacency. Neutralising India’s natural influence in its neighbourhood is clearly a high Chinese priority, and its actions in every neighbouring nation, (most recently Maldives) are confirmation, if confirmation was needed, that the String of Pearls concern is not in the realm of fanciful imagery but a strategic challenge to the India growth story.

Watching the frequent fluctuations in the graphs of India’s relations with its neighbours, South Asian scholars often pose the question, “Is India losing South Asia?” on the other hand, Indian diplomats with deep knowledge of India’s repeated efforts to improve relations with its neighbours usually pose the question the other way around, “Is South Asia losing India?” China’s increasing footprint in the region, and the penchant for India’s neighbours to frequently encourage it is a subject of continuing debate. There is only one way to address this reality, and that is for India to get its act together, adjust its diplomatic functioning style, policies and priorities, create an ambiance of mutual trust, expand the thrust of Atmanirbharta to include at least selected close neighbours including Nepal, and give them their rightful place as co-passengers on the journey towards speedy inclusive development. Neighbourhood First needs to be perceived by our neighbours as a living day-to-day Indian foreign policy priority and not just a slogan.

But if there is one country with which India needs to make a fresh beginning, it is Nepal.

It is in that hope that this book has been written.

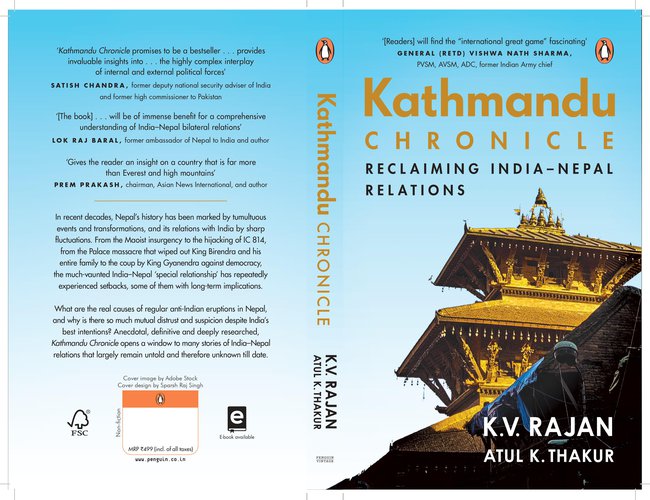

KV Rajan is India’s former Ambassador to Nepal and Atul K Thakur is a policy professional, columnist and writer with a special focus on South Asia. The above article is an edited extract from the authors’ recently published book, ‘Kathmandu Chronicle: Reclaiming India-Nepal Relations’ (Penguin Random House India, 2024) that offers unique insights on Nepal and India-Nepal Relations. The views expressed are personal.