Globally, modern environmentalism began in 1962 with Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring that highlighted the hidden but ubiquitous dangers of chemical biocides. Despite vitriolic attacks from the chemical industry, she did early on manage to get people to question their blind faith in market-driven “technical progress” that left behind a poisoned planet and an unhealthy populace. South Asia, being the colonialism-ravaged residue of that exploitative market, saw environmentalism as an intrinsic part of its freedom movements. Mahatma Gandhi’s “the world has enough for our needs but not enough for our greed”, his anti-industrial homespun khadi movement as well as his salt march against an exploitative tax system that maintained such an extractive regime was environmentalism long before its rise in the Industrial West.

Unfortunately, with independence, Gandhi was forgotten by India’s new rulers who strove to be like the enemy they just defeated as they pursued extractive market-led growth. The burden of social and environmental battles then shifted to the shoulders of a dwindling band of latter day Gandhians who continue to inspire some younger Indians with mixed results. Social reformers such asAcharya Vinoba Bhave, Baba Amte, Anna Hazare and several very local and lesser known figures have kept the Gandhian flame alive. Environmental campaigns from the Silent Valley in Kerala to the south, through Narmada Bachao Andolan in middle India to the Chipko Movement in the Himalaya continue to be the conscience of the nation even as Indian politicians in the parliament and assemblies changed from being mostly social workers and teachers just after independence to billionaires or even outright criminals today. That malaise is even more sordid and pronounced in Nepal with most top cabinet members soiled in scams and scandals (to say nothing of the recent “coups” in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Srilanka)!

Globally, things are not much better either. When it comes to violent conflicts such as Ukraine or Gaza, international organizations such as the UN seem powerless to do anything (except when it was big powers misusing UN’s legitimacy in Korea or Afghanistan). World Trade Organization has been rendered toothless; and when it comes to climate change, UNEP and the COPs are sinking to being confined to a week of platitudinous climate tourism with the rest of the world, especially the Industrial North, defending their economies by merrily burning more fossil fuel in the name of protecting their GDPs. The primary reason is that the roots of the current environmental crises, be it climate change, biodiversity loss or rising wealth inequality that is fueling growing social unrest, lie in the very nature of growth addicted markets and the governance structures in place to protect and promote them. Just trimming the edges is not going to change things much.

India’s Environmental Activism: Three Decades But Much Further To Go

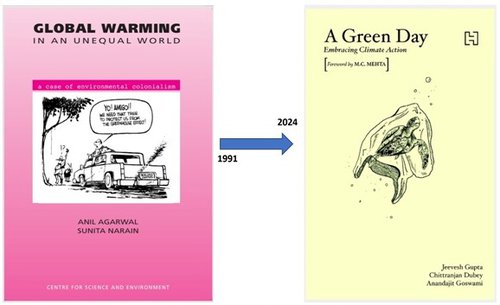

Addressing this angst among those more aware of the crisis is a new compilation of stories and reflections from India that lay bare the above conundrum {Jeevesh Gupta, Chittaranjan Dubey and Anandjit Goswami (eds.) A Green Day: Embracing Climate Action; Delhi: Hachette Press, 2024}. To those of us who have been witness to (and friends with) the works of earlier generation of Indian activists such as Anil Agarwal (whose Global Warming in an Unequal World plus Dying Wisdom and India’s disappearing tradition of water harvesting were seminal global contributions to the environmental movement), Anupam Mishra (whose work on traditional water harvesting structures in semi-arid India is even today an eye-opener),Sundarlal Bahuguna (his providing moral leadership to the Chipko movement still challenges conventional colonial forest management orthodoxy),D.K. Mishra ( with his campaign against plainly wrong “modern” flood control engineering that does more damage than good in the Ganga plains and beyond) and others, this collection forces some brutal reflections. Does it represent a movement forward or one in stagnation prompting a new generation to ask the same questions anew?

The book begins with a foreword by India’s legendary Public Interest Litigation (PIL) advocate M.C. Mehta who recounts his encounter way back in 1989 and subsequent activist journey in the courts of India against industries polluting rivers and groundwater to the detriment of the marginalized poor. It closes with an afterword by Extinction Rebellion co-founder Roger Hallam with his impassioned plea for action. He critiques India’s elites (including socio-environmental) for still being in thrall of Adam Smith and the exploitation-growth paradigm, and for its academics (like other global academics) for living in an ivory tower and failing to demonstrate any commitment to action that would actually matter.

In between are an assortment of accounts by Indian activists from Assam to the Western Ghats as well as international ones that movingly detail their journey and their battles. They range from disillusioned foresters and simple village folks to those operating at the more national level. The former began working at the very grassroots to bring about change, whether getting villagers to give up slingshots to protect birds, to support women in their anti-hooch campaigns or preventing plastic pollution. The latter worked to move courts and government machinery or even elite urbanites with NGOs and films to bring more broad-based changes.

Many of the international accounts, especially from Africa and Latin America are indeed moving and inspiring. And what makes them so is the lived experience of these activists. Both these regions were ruthlessly colonized, and formal political independence did not bring about the economic salvation that was expected of such freedom. Indeed, only the skin colours of the new masters changed from white to brown or black who then served as viceroys of exploitative capitalism’s centers in Paris, London or New York.

It is only now, with the rudimentary signs of the emergence of a new multipolar world order that heavily exploited regions are striking back – be it Brazil and Venezuela or Niger and Sahel countries – and taking economic control of their resources. It is too early – and highly doubtful – if these new aggressively nationalistic rulers will be environmentally friendly. As the history of India and its political class giving up on Gandhiism demonstrates, they will probably revert to ruthless market exploitation in the name of growth and development just as the white political masters were doing originally.

To wizened old-timers, the collection also displays significant shortcomings. It lacks a “roadmap” for easy reading which the editors should have provided. Nor is there a thematic thread between the different experiences. And it does not have a bio up front describing who the activists are, which does not often come out even after reading their pieces or the references listed. For a book on environmentalism coming out of India, neighbourhood views and success stories are sadly and completely missing. Nepal’s success stories with community forestry, water supply and electricity distribution show how alliances of social as well as bureaucratic activism can completely change the ecological landscape: thanks to such measures Nepal today has more forest cover than it ever did in its recent history.

I remember late Ramaswamy Iyer telling me, when I described to him these success stories in Nepal, how it may have been possible in Nepal (which was not politically colonized) but was impossible in India because the rigid resource exploiting laws of the British Raj, especially with forests and water, lives on. Pakistan’s experiences – as well as the rich debates about environmentalism there recounted by me in a different essay – would have been more valuable to reflect on in the Indian context than the essay on Ukraine which even the Indian government – whose import of Russian oil has jumped up from 3% to 43% in the last three years – would probably disagree with.

Hopefully a second future edition of this exercise would address these lacunae since India is the big center of South Asian gravity, and the environmental damage done within India rarely stays only within India.

Dipak Gyawali

Gyawali is Pragya (Academician) of the Nepal Academy of Science and Technology (NAST) and former minister of water resources.

- Behind Nepal’s Political Instability: Flaws in Loktantra’s Ethical Foundation

- Jul 15, 2025

- Navigating An Uncharted, Unravelling World Order

- Jun 19, 2025

- Overcoming Indo-Pak Conflict The Dara Shikoh Way

- May 13, 2025

- Re-Thinking Democracy: Why South Asians Are worried

- Mar 17, 2025

- Nepal’s Governance Mired In Endemic Corruption

- Feb 20, 2025