I. The Call of the Peaks

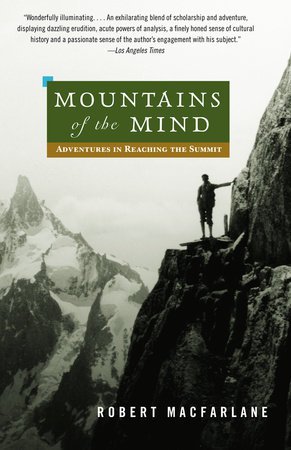

The Himalayas do not merely rise—they loom. At dawn, the first light licks the snows of Langtang and Annapurna, turning ridges into molten gold. These peaks, older than nations, older than gods, have borne witness to the rise and fall of empires, the ebb of pilgrims, and the whispers of poets. In his luminous work “Mountains of the Mind”, Robert Macfarlane writes that mountains are “a slow, grinding alchemy” of rock and time. But they are also mirrors. As South Asia navigates an era of fracture—climate collapse, border tensions, the feverish churn of geopolitics—the Himalayas offer more than postcard grandeur. They hold a lesson in unity, carved not in stone but in the stories, struggles, and shared breath of those who live in their shadow.

Consider Macfarlane’s observation: “Those who travel to mountain-tops are half in love with themselves, and half in love with oblivion.” The line captures the paradox of human ambition—the tension between individual glory and collective survival. Today, as glaciers retreat and political fissures widen, the question for South Asia is this: Can we, like climbers roped together on a serac, turn our gaze from oblivion to interdependence?

II. Cultural Cartography: The Peaks That Bind Us

To stand beneath Dhaulagiri or Kanchenjunga is to stand inside a story far larger than oneself. In Hindu cosmology, these are the abodes of Shiva and Parvati; in Buddhism, the realm where Milarepa meditated in icy caves. The Sherpa speak of yéty (Yeti), the “wild man” whose footprints—real or imagined—stitch together tales from Nepal to Bhutan. “Yeti sightings,” a Kathmandu-based anthropologist once joked, “are the original regional diplomacy—uniting skeptics and believers across borders.”

Literature, too, binds us to these slopes. When Nepali literary giant Laxmi Prasad Devkota wrote, “These peaks are my ancestors’ breath frozen in time,” he echoed a truth felt from Gilgit to Gangtok. Macfarlane calls mountains “archives of human longing,” and indeed, the Himalayas are our shared library. The same summits that inspired Tagore’s verses hum in the hymns of Pakistani Sufi poets. Even the colonial-era Survey of India, which mapped Everest as a trophy, could not sever the range’s cultural sinews.

Yet modernity has a way of fraying such threads. Today, a Nepali student in Pokhara might binge Korean dramas, while a Delhi teenager TikTok-dances to Bollywood remixes. The Himalayas, though, remain a fixed point—a reminder that beneath the noise of the present lies a bedrock of common myths, migrations, and memory.

III. Crevasses of Geopolitics: Navigating the Icefall

If the Himalayas are a metaphor, then South Asia today resembles a glacier—deceptively solid, riddled with hidden crevasses. Territorial disputes simmer: India and Pakistan spar over Siachen’s “white hell”; Nepal and India tangle over Kalapani. Water, the lifeblood of 1.8 billion, becomes a bargaining chip. “Summiting Everest,” a veteran Sherpa guide once told me, “is simpler than a SAARC summit.”

History, however, offers footholds. Emperor Ashoka’s edicts—etched in rocks from Kandahar to Odisha—called for unity in diversity millennia before the EU. Medieval traders on the Silk Road swapped spices and Sufi ballads, not tariffs. Even the British, while drawing maps in distant London, could not fully silence the cross-border hum of folk songs. Macfarlane writes of risk as inherent to mountains: “To refuse the mountain’s challenge is to refuse ambition itself.” Our ambition today must be to confront the crevasse—not with ropes cut, but with ropes shared.

Imagine if SAARC summits borrowed from mountaineering ethics. Sherpas and climbers survive the Khumbu Icefall by relying on fixed lines and reciprocity. Why can’t nations anchor their own ropes? Joint climate projects, like the ICIMOD-led glacier monitoring, show it’s possible. When Pakistan sent aid to India during the 2021 oxygen crisis, it was a flicker of this spirit—a hand stretched across the ridge.

IV. Climbing Lessons: The Rope, The Rhythm, The Summit

Every mountaineer knows three truths.

First: The rope is sacred. When Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary summited Everest in 1953, they did so tethered—a partnership that transcended empire and identity. Today, South Asia’s “rope” could be a green energy grid linking Bhutan’s hydropower to Bangladesh’s factories, or a revived Buddhist circuit connecting Lumbini to Bodh Gaya.

Second: Acclimatise or perish. Climbers ascending Everest pause at Base Camp, then Camp I, then II—adapting to the thinning air. Trust-building between nations demands the same patience. Swap paranoid headlines for student exchanges; let Lahore’s qawwals sing in Kathmandu’s alleys. As Narayan Wagle’s “Palpasa Café”—a novel of Nepal’s civil war—reminds us, reconciliation is “the art of listening to the same story from the other side of the hill.”

Third: Summit fever kills. Macfarlane warns of climbers so obsessed with the peak they abandon companions. The lesson? Regional unity cannot be another flag-planting race. It requires the humility of the Sherpa, who summit Everest repeatedly not for fame, but as “work”. “No one summits Everest,” a Thamel trekking agent quipped, “by arguing over who owns the ice axe.”

V. The View from the Peak: A Vision in Thin Air

From the top, borders blur. The Indus and Ganges, born of the same snows, snake across plains. The vision is clear: A South Asia where climate treaties replace troop deployments; where festivals like Dashain and Baisakhi are celebrated as cross-border harvests; where the Himalayas are not a wall but a watershed—of ideas, equity, and shared oxygen.

This is no utopian hallucination. Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness index—rooted in Buddhist ecology—inspires global economists. Nepal’s community-led forestry revived 2.3 million hectares of land. Imagine scaling these models. Let Pokhara host a regional climate university; let Karachi’s artists and Paro’s weavers collaborate on a “Himalayan textile trail.”

Macfarlane writes, “The mountain… is a mirror in which the mind might see itself.” In that reflection, we must glimpse not just national identities, but a regional consciousness—one that sees Pakistan in Nepal’s terraced fields, Bangladesh in Uttarakhand’s rivers, and Sri Lanka in Goa’s monsoon clouds.

VI. The Descent: Carrying the Summit Home

The hardest part of any climb is the descent—returning to the world without forgetting the view. Nepal, as the Himalayas’ custodian, is uniquely poised to lead this return. Host dialogue not in air-conditioned halls, but in Mustang’s caves or Janakpur’s temples. Revive the Kailash-Mansarovar Yatra as a pilgrimage of pluralism.

As T.S. Eliot wrote, “What we call the beginning is often the end. And to make an end is to make a beginning.” Let us begin by trading hubris for humility, suspicion for shared summits.

The Himalayas, after all, were never climbed alone.

*Zakir Kibriais a writer and nicotine fugitive (once successfully smuggled a lighter through 3 continents). Entrepreneur | Chronicler of Entropy | Cognitive Dissident. Chasing next caffeine fix, immersive auditory haze, free falls. Collector of glances. “Some desires defy gravity. ”Email: zk@krishikaaj.com

- Digital Colonialism 2.0: How Global Platforms Redefine Truth in Nepal and Beyond

- Apr 10, 2025

- Trump’s Tariffs and the Dawn of Multipolarity: Implications for Nepal

- Apr 06, 2025

- “Mountains Of The Mind" – When Western Obsession Meets Himalayan Timelessness

- Apr 01, 2025

- How Ukraine War Made Nepal’s Momo 30% More Expensive

- Mar 28, 2025

- Democracy as Disruption: A Rancièrean Reckoning in Nepal and South Asia

- Mar 24, 2025